Understanding the Differences and Choosing the Right Approach

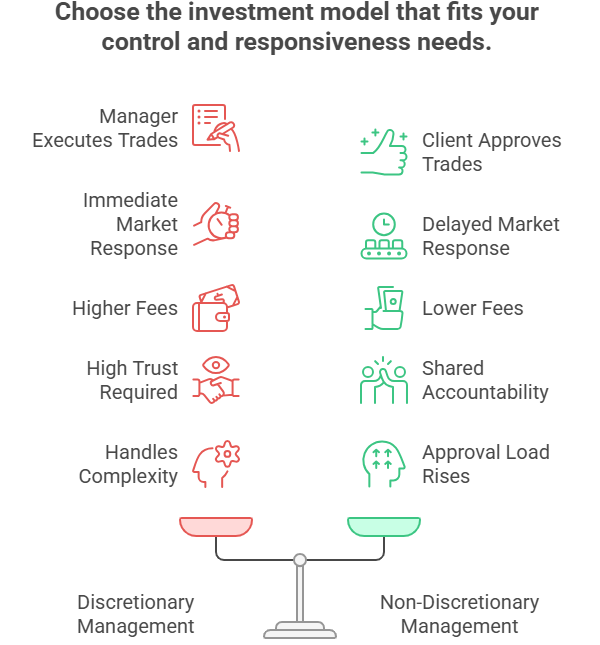

Most investors do not argue about “models.” They argue about something simpler. Do you want to be the person who approves every move, or do you want a professional to make calls on your behalf and tell you what they did after the fact? That is the heart of discretionary vs non-discretionary investment management.

In a discretionary setup, you agree on the rules up front and the manager can trade within that mandate. In a non-discretionary, or advisory account setup, the advisor brings recommendations and you give client approval for each trade. Neither approach is automatically smarter. They just fit different personalities, governance setups, and levels of complexity.

The choice matters because it changes how your portfolio behaves when life gets busy or markets get jumpy. It affects investment control, how quickly decisions get executed, how much trust you need to place in a manager, what kind of oversight you will realistically maintain, and what the ongoing cost and effort looks like for you or your committee.

In the sections below, we lay out the key differences in a clear comparison table, then give you a decision checklist to make the choice practical. We also cover hybrid approaches that mix both models, and portfolio oversight habits that keep you informed without forcing you into the weeds.

What is discretionary investment management

Discretionary investment management means you give an advisor or manager the authority to make trades in your account without asking you for approval each time. You are not handing over a blank check. You are agreeing on the rules first, then letting the manager act inside those rules.

Those rules usually live in an investment policy statement, or IPS, and they matter more than many people realize. The IPS sets the boundaries around risk level, return objectives, liquidity needs, eligible investments, concentration limits, tax constraints, and anything else that should shape day to day decisions. If the mandate is vague, discretionary management can feel like a black box. If it is clear, it becomes a practical way to delegate execution while keeping intent and guardrails in place.

The upside is speed and convenience. Decisions can be executed when they need to be executed, and you are not stuck reviewing every trade in the middle of your day. Many investors also like the professional discipline that comes with a managed account, especially when markets are noisy and emotions are high.

The trade-off is investment control. You are relying on trust, process, and oversight rather than direct client approval. Discretionary portfolio management can also come with higher minimums or higher fees because the manager is taking on more responsibility and a more operationally demanding service model.

A simple volatile market example makes the point. If a sharp selloff creates a chance to rebalance, a discretionary manager can act immediately within the IPS. In a non-discretionary setup, the same trade may sit waiting for approval, and timing can change the outcome even if the idea is sound.

What is non-discretionary advisory investment management

Non-discretionary investment management, often called an advisory account, means the advisor makes recommendations but cannot place trades without client approval. You stay in the decision seat. The advisor brings ideas, explains the rationale, and you decide what gets executed and when.

The benefit is investment control and transparency. You see the proposed trades before they happen, you can ask questions, and you can shape decisions in real time, which many investors and committees prefer. For family offices and institutions, this model can also fit governance reality, especially when policies require documented approvals or when multiple stakeholders want to weigh in.

The trade-offs are speed and time. Execution is only as fast as the decision cycle, and the workload does not disappear. Someone has to review recommendations, schedule calls, document decisions, and respond when markets move. Over time, that effort can become a bottleneck, especially in portfolios that require frequent rebalancing, tax-aware adjustments, or manager changes.

Approval delays are not a theoretical issue. If markets gap down in the morning and an advisor recommends trimming risk or adding exposure, the difference between acting now and acting two days later can be meaningful. In a non-discretionary investment model, outcomes can hinge on availability and process, not just the quality of the advice.

Discretionary vs non-discretionary key differences with a comparison table

When you strip away the labels, the difference is about authority and workflow. This table gives you a quick way to compare discretionary vs non-discretionary across the factors that usually drive the decision in real life.

| Comparison area | Discretionary investment management | Non-discretionary (advisory) investment management |

|---|---|---|

| Decision authority | Manager has authority to trade within the mandate | Advisor recommends, client approval required for each trade |

| Execution speed | Faster, can act immediately within guidelines | Slower, depends on approval timing and availability |

| Client involvement and time | Lower day-to-day involvement, more review after the fact | Higher involvement, requires ongoing review and decisions |

| Trust requirement | Higher, relies on mandate plus manager judgment | Moderate, trust still matters but decisions stay with the client |

| Fees and cost structure high-level | Often higher due to delegated execution and responsibility | Often lower, but time cost shifts to client or committee |

| Accountability and fiduciary dynamics | Manager is accountable for execution within the mandate | Accountability is shared, since approvals are part of the process |

| Portfolio complexity fit | Often better for complex portfolios that need frequent action | Can work, but complexity increases the approval burden |

| Governance fit | Fits individuals and teams that can delegate with oversight | Fits committees and stakeholders who require formal approvals

|

Control and decision rights

The core distinction is who can say yes to a trade. In discretionary portfolio management, you set the mandate and the manager executes within it. In a non-discretionary investment model, the advisor can propose, but client approval is what turns a recommendation into an actual trade. If you want maximum investment control, non-discretionary keeps you closest to the steering wheel.

Speed and responsiveness

Markets do not wait for calendars. Discretionary management can respond immediately when rebalancing is needed, risk needs to be reduced, or an opportunity appears inside the mandate. In an advisory account, execution depends on how quickly you or your committee can review and approve the recommendation, which can be fine in calm periods and painful during fast moves.

Cost and fees

Fees vary by firm and scope, so it is safer to think in terms of what you are paying for. Discretionary management often costs more because the manager is taking on execution responsibility and more day to day work. Non-discretionary arrangements can be less expensive, but they shift part of the operational burden to you, meaning time, attention, and process.

Trust, oversight, and accountability

Discretionary management requires more trust because you are delegating action, not just analysis. Oversight still matters, but it happens through review of results and adherence to the mandate rather than pre-trade approvals. In a non-discretionary model, accountability is more shared because decisions involve both the advisor and the client, and oversight is built into the approval process.

Complexity and customization

Complexity is where delegation often starts to look attractive. Multi-asset portfolios, alternatives, multiple accounts, tax constraints, or multiple managers can create a steady stream of small decisions that add up. Discretionary management can handle that flow without turning each adjustment into a meeting. Non-discretionary can still work, but the approval load rises quickly as complexity increases, and portfolios can drift while decisions wait for review.

How to choose decision framework

This choice usually gets clearer when you stop thinking about labels and start thinking about your week. Use the checklist below to pressure test what you actually want to own versus what you want a manager to handle.

☐ How involved do I want to be in day to day portfolio decisions?

☐ How quickly do decisions need to happen in my situation?

☐ Do I realistically have the time to review and approve every trade?

☐ Am I comfortable giving a manager authority to act within a written mandate?

☐ Do I have enough trust in the person and process to delegate execution?

☐ Would I rather collaborate on each decision, even if it slows things down?

☐ Is my portfolio complex, for example multi-asset, alternatives, multiple accounts, or multiple managers?

☐ Do tax constraints or cash needs require frequent adjustments and rebalancing?

☐ For a family office, who is responsible for approvals when the main decision maker is unavailable?

☐ For institutions, do we have governance bandwidth to approve decisions quickly, or does the committee cycle create delays?

In general, more “yes” answers to speed, time constraints, and complexity point toward discretionary investment management, where the mandate does the controlling and the manager does the executing. More “yes” answers to hands on involvement and preference for pre trade visibility point toward a non-discretionary advisory account, where client approval stays at the center of the workflow.

Hybrid approaches using both models

Most real portfolios do not live at one extreme. A hybrid approach is common because different assets and decisions benefit from different levels of delegation and investment control.

A typical setup is a core and satellite structure. The core is run under discretionary portfolio management, usually a diversified allocation that needs consistent rebalancing and disciplined execution. Around that, an advisory account sleeve can hold more opinionated positions, cash planning moves, or specific manager selections where you want more involvement and client approval.

Family offices often land in a similar place for practical reasons. They may delegate public markets or a balanced mandate to one or two managers, then keep direct deals, private investments, or concentrated legacy positions under tighter control. That split can reduce the day to day approval burden while still letting the family own the decisions that feel most sensitive or complex.

Institutions use hybrids as well, especially when governance is shared. One common pattern is an outsourced sleeve, such as an outsourced CIO (OCIO) mandate, for parts of the portfolio where speed and coordination matter, paired with committee-controlled sleeves where approvals and policy oversight remain central. The benefit is that the organization can delegate execution where it helps, without giving up the governance structure that stakeholders expect.

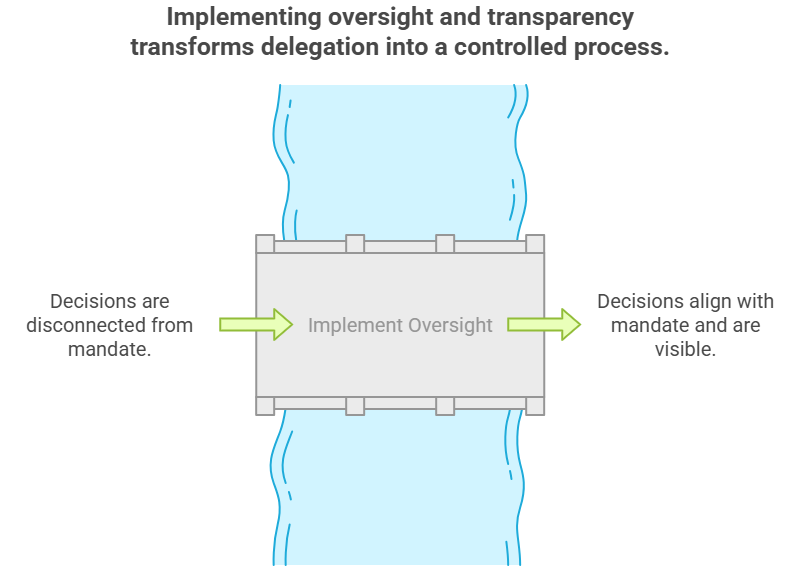

Oversight and transparency regardless of model

Good oversight starts with a clear IPS or mandate. That is what turns a relationship into a repeatable process. It should spell out objectives, risk limits, constraints, liquidity needs, eligible assets, and how performance and risk will be judged, so you are not debating expectations after the fact.

Next is cadence. Most investors and committees do better with a simple rhythm they actually follow. Review performance in context, not as a single number. Look at exposures, concentration, and portfolio drift versus targets. Pay attention to fees and total costs, especially when you have multiple managers or layered vehicles, because cost leakage is easy to miss when it is spread across accounts.

Governance is the part people skip until something goes wrong. Decide who reviews, how often, and what triggers escalation. Triggers can be as simple as a manager deviating from the mandate, a drawdown beyond tolerance, unexpected style drift, or repeated surprises in reporting or fees. When those rules exist up front, conversations get more productive and less emotional.

Consolidation is where oversight can break down, especially for family offices and institutions with multiple accounts, managers, and asset classes. If data is coming in from different custodians and reporting formats, it becomes harder to maintain a single view of performance and exposures, and issues can hide in the seams between reports. Many families and organizations use consolidated reporting tools such as FundCount to aggregate data across accounts and managers and maintain one view of performance and exposures.

Whether you choose discretionary or advisory, the goal is the same. You want delegation to feel controlled and visible, not opaque, and you want decisions and outcomes to stay connected to the mandate you agreed to.

FAQ

What is a discretionary investment account?

A discretionary investment account is one where the advisor or manager can place trades without asking for client approval each time, as long as they stay within the agreed mandate. The mandate, often documented in an IPS, sets the boundaries around risk, objectives, and constraints.

What is a non-discretionary advisory account?

A non-discretionary, or advisory account, is one where the advisor recommends trades but the client must approve each transaction before it is executed. This model keeps investment control with the client and makes collaboration more direct, but it can slow execution.

Which is better discretionary vs non-discretionary?

It depends on what you value most in your own situation. Discretionary tends to fit investors who want speed, less day to day involvement, and can trust a manager to act within a clear mandate. Non-discretionary tends to fit investors and committees who want pre-trade visibility and are willing to spend time approving decisions.

Is discretionary management always more expensive?

Not always, but it is often priced higher because the manager is taking on more responsibility and doing more ongoing execution work. The more practical comparison is total cost and time cost, since advisory models can shift some burden to the client or committee.

Can I switch from advisory to discretionary later?

Yes, many people start in an advisory account while they build comfort with a manager’s process, then move to discretionary once the mandate is clear and trust is established. Switching works best when the IPS is updated and reporting expectations are reset so oversight stays consistent.

How do institutions handle this OCIO vs committee approvals?

Many institutions use delegated investment management through an outsourced CIO (OCIO) or similar model for sleeves where speed and coordination matter, while keeping other decisions under committee control. The split usually reflects governance bandwidth, policy requirements, and how quickly approvals can realistically happen.

How do I maintain oversight if I delegate decisions?

Oversight starts with a clear mandate and a consistent reporting cadence that reviews performance, exposures, drift, and fees. You also need defined escalation triggers so surprises do not linger, and a consolidated view across accounts and managers so issues do not hide in disconnected reports.